How displaced women in Borno are regaining their say in childbearing

BY HADIZA IBRAHIM NGULDE, JULY 03, 2025 | 09:20 PM

Aisha Usman once ran a business she operated on a credit system through buying flour from the market, then making and selling Ɗanwake, a local meal. Afterwards, she would settle her debts and keep the profits to sustain her family.

Aisha, who lived with her eight children and husband in her hometown of Monguno, Borno State, didn't know what it meant to starve. This was over a decade ago, before Boko Haram's violent insurgency ravaged the area, killing many people and displacing thousands like Aisha.

Now, living at the El-Miskin internally displaced persons (IDPs) camp in Maiduguri, the Borno State capital, Aisha had lost the economic stability that once kept her family happy.

With eleven children after birthing three more in the camp, and her family constantly battling with starvation, Aisha saw another tragedy unfold. Her daughter was raped in the camp and subsequently gave birth to a child. After the incident, Aisha's husband, who was meant to be a pillar of support, left her and their children to face these challenges alone. “It was too much for him to bear,” Aisha recounted with tears streaming down her face.

Since then, her husband's presence has been infrequent. Just as she struggles to cater for the family, Aisha also realised the need to regain control over her body, deciding how and when to have more babies for her own physical and economic well-being.

This decision came after she learned about family planning through Médecins du Monde (MdM), an organisation dedicated to bridging health inequities affecting the most vulnerable in conflict-ridden areas. In 2017, MdM began organising monthly sessions at the El-Miskin camp to educate women on childbirth spacing.

Caption:El-miskin IDP camp, Maiduguri, Borno state

Rebranding family planning

In Borno State, many women view family planning as simply limiting the number of children, often to a figure they consider unusually low. According to National Population Council estimates, the state has an annual population growth rate of 3.4%, with women of childbearing age forming 22.9% of the population. For this reason, the approach is entirely different and family planning now goes by a different name: childbirth spacing.

Abbaram Sani, the family planning coordinator of Maiduguri, explained that they stopped using the term “family planning” because it often provokes religious and cultural backlash.

“We usually tell couples that even if they want to have as many children as they can, they should have them, but let them give space between births to avoid maternal health concerns,” she stated.

Caption: Abbaram Sani, Family planning provider, Maiduguri Metropolitan Council,at the Yerwa Primary health care center

For Aisha, childbirth spacing is about physical and psychological healing, not simply a matter of rest. She shared that with food becoming more difficult to get, she cannot afford to have more children. “I want to focus on how to take care of my family, rather than having more children,” Aisha noted.

As the women's leader of El-Miskin camp, a role through which she directly connects with many IDPs and also earns their trust, Aisha now encourages other women to adopt childbirth spacing for their well-being.

Caption-Aisha Usman, in the hall where she once advocated for Child birth spacing at the El-Miskin IDP camp

On the day when this reporter visited Yerwa Primary Health Care Centre (PHC) in Maiduguri, some women walked into the facility with courage, while others stepped in with their faces softly veiled, to take control of their reproductive health. Abbaram, who attends to their requests at the PHC, has observed that many women no longer hide their faces when seeking family planning services, and they now present their requests confidently.

At Dalaram Clinic, in the Jere area of Borno, family planning supplies once expired in storage due to low demand in previous years. Today, this has flipped, with clinics encountering supply shortages due to a considerable increase in demand. The Borno State Primary Healthcare Development Board also reports a notable increase in family planning service uptake across the state in 2024, with 269 facilities now offering these services.

A health worker wearing a child birth spacing advocacy apparel at the Dalaram clinic in Jere local government area of Borno state.

Reproductive rights and safety

Access to family planning services is only one part of the picture. Many women in official and unofficial camps as well as host communities in Maiduguri face the looming horrors of rape and domestic violence.

As both a family planning provider and a focal person for gender-based violence (GBV) cases, Abbaram has witnessed the intersection of women's control over their bodies and safety. “We get more cases of domestic violence than rape,” she explained. “Women who are beaten, verbally abused, denied feeding or even access to antenatal care by their husbands all confide in me.”

For rape cases, Abbaram added that they have emergency pills to give victims within 72 hours of the incident to prevent unwanted pregnancies. She clarified that these are primarily used for emergency rape cases, as they do not consider it a method of family planning.

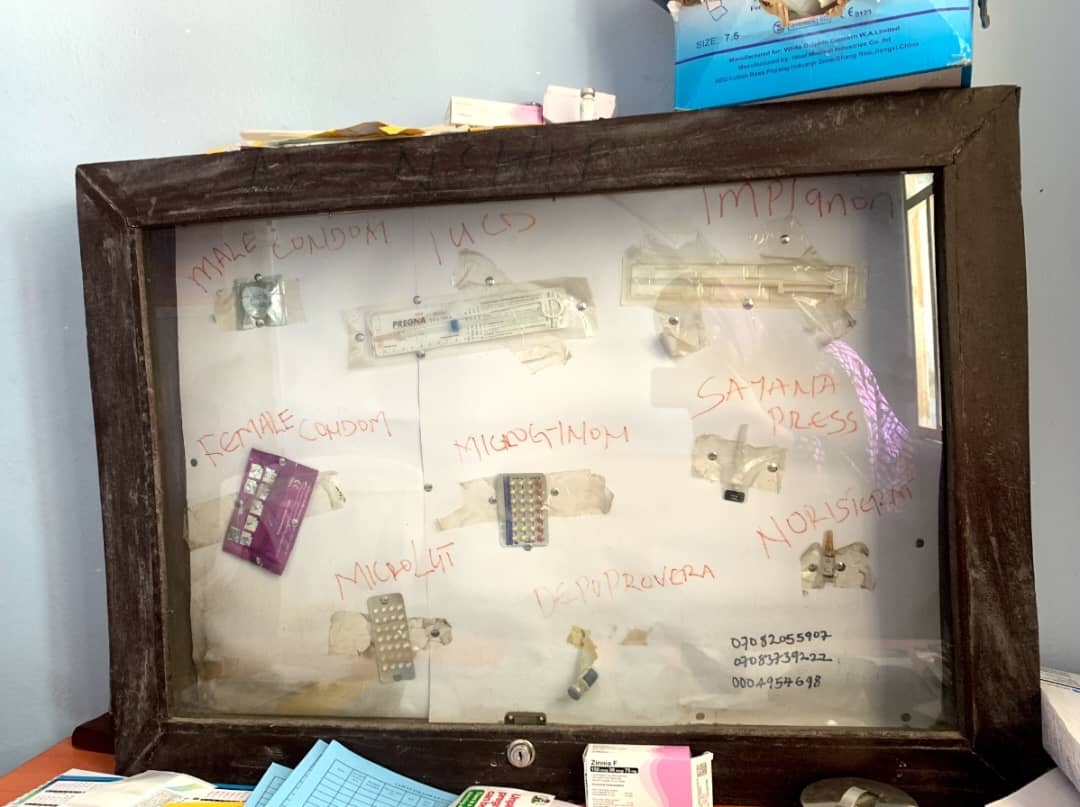

Caption:Various methods of child birth spacing plans available at the Yerwa primary health care center

The change was slow but steady as both women and men from different communities of Borno kept spreading the gospel of childbirth spacing through various means: monthly meetings in IDP camps, targeted in-reach and outreach advocacies, and regular radio and television broadcasts.

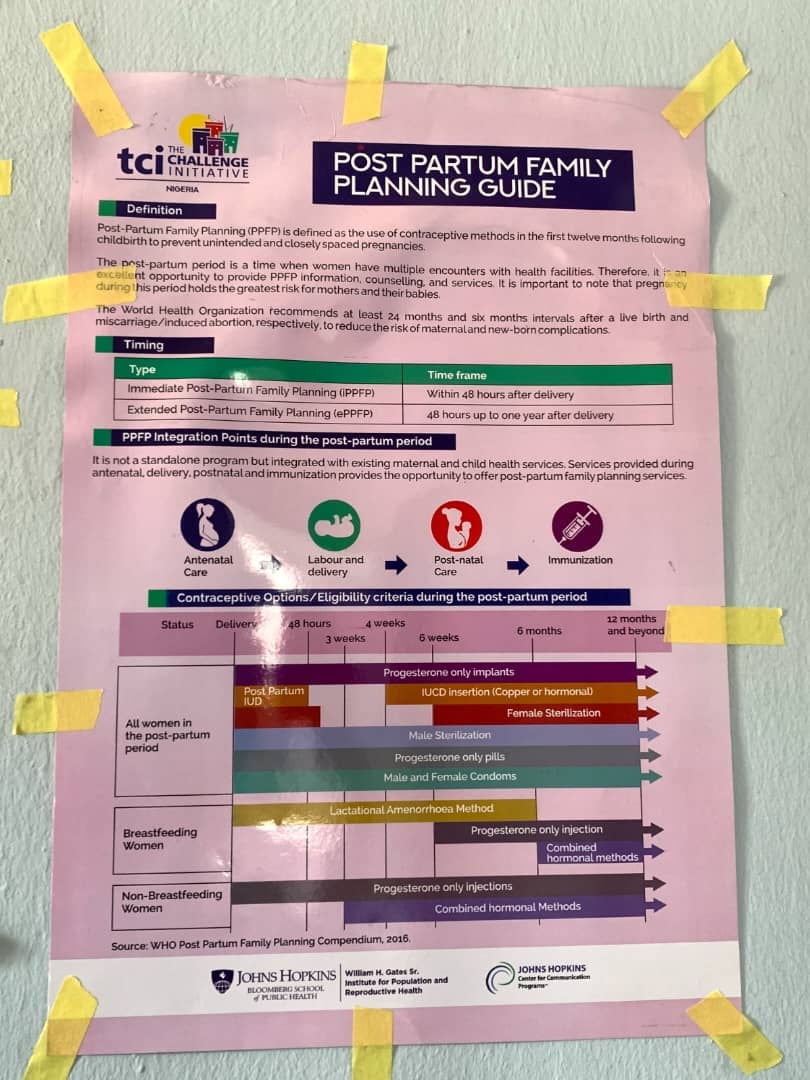

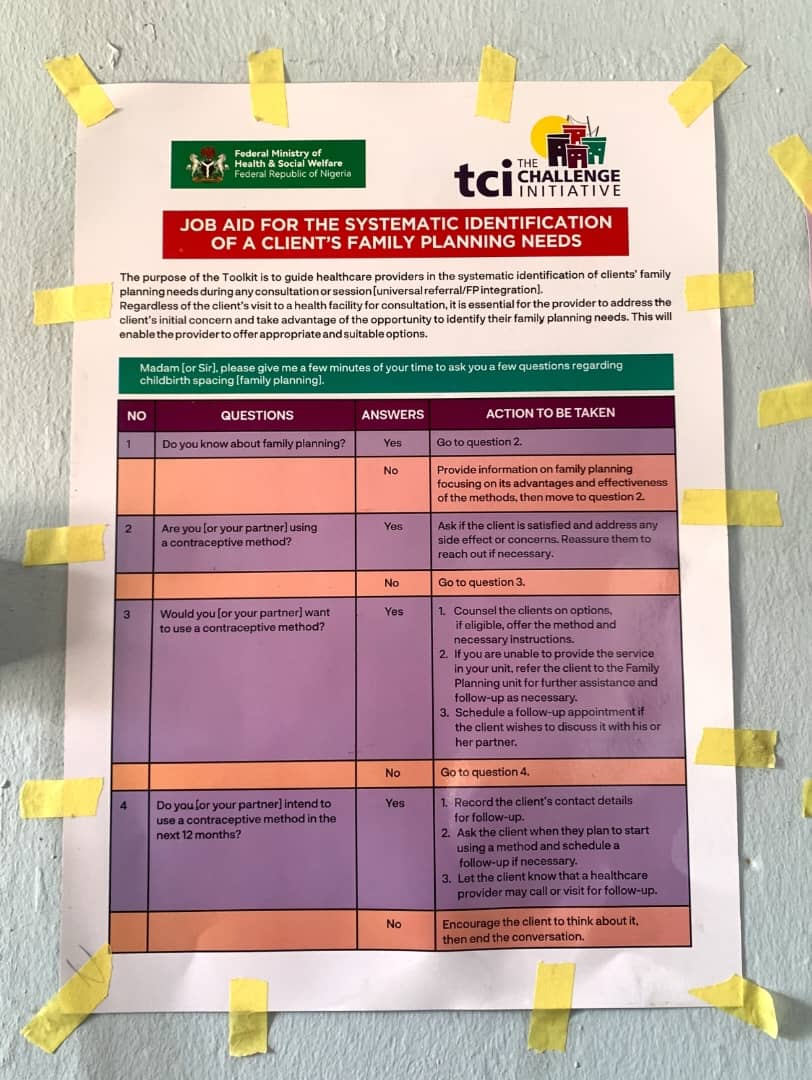

Since beginning operations in Borno State in 2022, The Challenge Initiative (TCI), has spearheaded advocacy for family planning/childbirth spacing. Partnering with the Borno State government, TCI focuses on high-impact practises that improve health outcomes, are cost-effective, and can be scaled regionally.

Caption:TCI’s infographic poster at the Yerwa primary health care center in Maiduguri, Borno state

“We support the state government to implement high-impact practices in childbirth spacing,” said Dr. Yusuf Ahmadu, TCI state program manager. “There are also men who are now champions, going into communities to tell other men the benefits of childbirth spacing.”

The involvement of men is key, as many women still need their husbands’ approval before accessing the services. TCI addresses this by organising community dialogues with district heads and community chiefs, most of whom are men, to promote family planning as a health necessity, not something morally questionable.

Youth and women groups, along with traditional leaders, also served as trusted figures in their communities. They spoke in a way people easily understood while advocating for taking breaks between pregnancies.

Fatima Mohammed Mala, 21, was on a birth control plan, but with her 14-month-old toddler already taking her first steps, she felt it was time to conceive again. This made her initially reluctant to attend her follow-up appointment, which she deemed unnecessary. Yet, her husband insisted that it was important for her well-being.

When Mairo Bukar came to Yerwa PHC for her childbirth spacing follow-up, she shared that her family had decided it was time for her to stop having children due to health concerns.

“I have seven children already, and I am hypertensive and also tired of having more children. My husband supports this, so for four years now, I've used an Inter-uterine Contraceptive Device (IUCD) and now I'm on the Noristerat injection,” Mairo told this reporter.

Caption: Mairo Bukar at the Yerwa primary health center, in Maiduguri for her Family planning follow up appointment

What shapes the approach

They say the easiest way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. For Borno, the easiest way to its heart is through its religion. Both Muslims and Christians in the state hold religious leaders and scriptures in very high regard. And that's what shapes their acceptance of childbirth spacing.

This holistic approach involved propagating childbirth spacing in churches during fellowships and conferences, and in mosques during sermons and Islamic study circles

Reverend Fali Wajauba, Vice Chairman of the Borno State Pentecostal Fellowship of Nigeria, stated that the trust Christian faithful place in their religious leaders makes it easier to integrate the childbirth spacing message into existing marriage counseling programs for intending couples. He also emphasised that this guidance is specifically for those in conjugal relationships.

“We do not encourage unmarried people to engage in premarital sexual relations,” he asserted. “For in Christianity, having premarital sex is a sin in the eyes of God, and only people who engage in conjugal relationships would need family planning.”

The approach differed slightly among the Muslim populace. Initially, bringing up topics like family planning during mosque sermons and in Islamic schools was frowned upon. This resistance, however, didn't last long. Abdu Baba Goni, the Chairman of JIBWIS in Borno, recalled incidents where individuals in his congregation refuted the message, claiming it was inappropriate for the place and context.

“As I began, a man abruptly stood up and challenged me and what I was saying. And another one soon joined him and then others followed,” Abdu narrated.

Understanding his congregation's disposition, Abdu wisely halted his initial message. In a subsequent sermon, he built a firmer foundation, using Qur’anic verses to show Islam’s comprehensive guidance on marital and family matters.

To foster acceptance and increase compliance, scriptures were strategically used. Biblical verses like Genesis chapter 1, verses 26-28, Timothy 5:8, and Psalm 127 verse 3 promote the family as a unit and children as blessings from God. More precisely, Qur'an chapter 46, verse 15 and Qur'an chapter 31, verse 14, recommend a period of 24-30 months for childbearing and weaning. “This is about the same duration we advocate for even in modern childbirth spacing methods,” Abdu explained.

With these efforts, the number of women seeking family planning services at PHCs has increased significantly. For example, two facilities this reporter examined, Yerwa PHC and Daralam Clinic, showed an average of 150-200 women each month. Aisha Musa Timta, Borno’s state family planning coordinator, noted that even with Borno State's unique religious and cultural background, the State Primary Healthcare Development Board is ensuring these services are available for all, including adolescents, at PHCs across all 27 local government areas in Borno. This reporter couldn't independently verify the claim.

Shortfalls

While significant strides have been made to promote child birth spacing in Borno, challenges remain. Fear and misconceptions, firmly embedded in the people’s mindset persists, leading some to wrongly believe that family planning involves aborting unborn children or inserting a substance that will prevent a woman from giving birth. Health workers said erasing such a deeply ingrained belief is difficult.

Firdausi Bulama, for instance, expressed her fear of opting for a long-term childbirth spacing method, citing an unpleasant experience from her neighbour.

“She had the implanon and she experienced discomfort on the arm where it was inserted,” Firdausi stated. “Initially, I also encouraged her to see if it would subside, but she insisted she couldn’t. That is why I won’t try. It scares me”

A more large-scale hindrance to the advocacy and promotion of family planning and childbirth spacing in Borno State is a decline in funding and the withdrawal of support from non-governmental organisations who championed the cause.

This has slowed the momentum of the programmes, leading to a shortage of commodities in PHCs where the services are rendered. It has also resulted in limited access to family planning services, especially for women living in IDP camps.

In the same vein, consumables essential for administering these services, like gloves, xylocaine, and iodine, tend to be scarce due to uneven prioritisation in distribution to health facilities.

Abbaram explained, “We have a surplus amount of implants, but for the things we'll use to carry out the procedure, without adequate supply, the clients have to buy.”

In the worst cases, clients even resort to purchasing their injectables and IUDs from external pharmacies because of these shortages. This added cost has deterred many from continuing their birth control, causing them to skip follow-up appointments.

Adding to the burden, a health worker who chose not to be named highlighted that free family planning services aren't truly free. Clients pay not only for the commodities but also for the service itself, with costs ranging from as low as N500 to as high as N3,500 in some facilities, depending on the preferred spacing plan.

This story is produced with support from Centre for Communication and Social Impact (CCSI).

Appeal for support

Conflict Reporting is dangerous and risky. Our reporters constantly face life-threatening challenges, sometimes surviving ambushes, kidnap attempts and attacks by the whiskers as they travel and go into communities to get authentic and firsthand information. But we dare it every day, nonetheless, in order to keep you informed of the true situation of the victims, the trends in the conflicts and ultimately help in peace building processes. But these come at huge cost to us. We are therefore appealing to you to help our cause by donating to us through any of the following means. You can also donate working tools, which are even more primary to our work. We thank you sincerely as you help our cause.

Alternatively, you can also email us on

info@yen.ng or message us

via +234 803 931 7767